7 Ways to Prevent Your Culture Change from Failing

(for the same reason as New Year’s Resolutions)

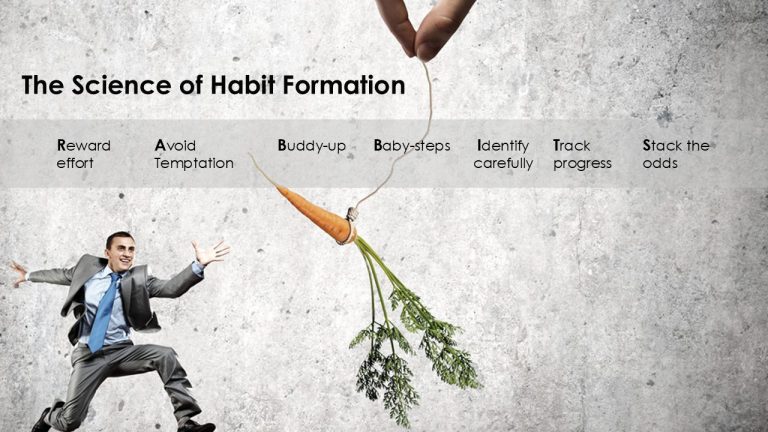

Habits are like RABBITS: Using Habit Formation to Drive Culture Change

Contrary to the popular belief that there is a “magic number” of days to develop a habit, recent research suggests that it may take months to form the habit of going to the gym, but only weeks to develop the habit of handwashing in a hospital (Buyalskaya et al., 2023). This becomes important when we think about culture as the collective habits of a group because it means that complex new behaviours may need to be repeated for a significant period of time before they become second nature (or ‘the way we do things around here’). In this article we discuss why Habits are like RABBITS and name our seven new RABBITS for 2025 (the seven most current science-based supports for behaviour change) …

Once again, please indulge the rabbit analogy: European rabbits were introduced into the Australian wild in 1859 by Thomas Austin, a wealthy settler who lived in Victoria, Australia. He had 13 wild European rabbits shipped to him from across the world and set them free on his estate, so that he could hunt them. From this one backyard sanctuary, it took only around 50 years for these invasive creatures to spread across the entire continent, causing hundreds of millions of dollars of damage to agriculture each year and threatening the extinction of over 300 species of local fauna and flora. According to the National Geographic and the Centre for Invasive Species Solutions, there are now well over 200 million rabbits in Australia. That’s close to 10 rabbits for every human being, so where are they all?

Well, the reason you didn’t know you had a 10:1 rabbit ratio is that they spend a fair bit of their time underground in warrens that can be up to 3 metres deep and 45 metres long. This is where rabbits make baby rabbits (‘kits’) with a single mother capable of producing over 180 offspring in 18 months. That combination of stealth reproductive ability makes them the perfect analogy for human habits. We are habit-making machines, acquiring literally millions of micro-habits that enable us to do most things on autopilot, from cleaning your teeth to walking and talking, typing or driving a car. Each of these skills is a cluster of complex movements that have been habituated through repetition. According to the US National Science Foundation (2005), the average person has between 12,000 and 60,000 thoughts per day, 95% of which are repetitive and largely unconscious. This propensity to generate vast numbers of thoughts of which we are largely unaware, makes our habits comparable to rabbits. Our habits become so well ingrained that they can be entirely performed by our subconscious mind, without imposing any kind of cognitive load on our conscious thought. Think about how much conscious effort you put into reading this and whether you crossed your legs a certain way, or how you located and scratched that itch a moment ago (if you can even remember doing it, that is!)

Contemporary research suggests that we can cash in on this natural talent, applying it not only to personal, but also to organisational development in interesting ways:

1. In organisations, our most sought-after ‘skills’ are, in fact, habitual behaviours that can be learned. Through daily practice, these behaviours can become automatic, gradually requiring less and less conscious effort to execute, until they have become entirely unconscious ‘capabilities’; and

2. When the collective habits of a group become ‘ways of working’ they are the embedded culture of the group – implicit, routinised symbolic systems of meaning that influence our social interactions (Flesher Fominaya, 2014).

At either the individual or organisational level, habits free up cognitive capacity, as we learn to do things automatically and our active attention is then able to be focussed on whatever complex new activity is most deserving of our time. Habits are cue-dependent, automatic responses formed through repetition in consistent contexts (Gardner & Rebar, 2019; Lally & Gardner, 2013). They are formed by addressing beliefs, setting goals, planning, establishing cues, reinforcement, repetition, and progressing to automaticity (Harvey et al., 2020). Once formed, habits are much more able to sustain behavioural change because they are less dependent on conscious motivation (Orbell & Verplanken, 2020).

Continuing with our RABBITS analogy, here are some evidence-based ways to establish a new habit (be that a cultural change, or a New Years’ Resolution):

1 . Reward effort, and not just success: According to BJ Fogg, director of the Behavior Design Lab at Stanford University and the author of Tiny Habits, making new behaviours a positive experience is critically important because, “Emotions form habits.” Positive reinforcement should begin immediately with your own narrative and self-exhortation. Using the analogy of weight loss, instead of waiting to get on a scale to measure your progress, you should be telling yourself that your new behaviour is getting you closer to your goals and that it feels great to be doing it. Celebrate effort and small victories, not just the end result.

2. Avoid temptation: “Psychology and neuroscience define habit as a type of decision process in which the same behaviour is executed in the same context, regardless of the outcome” (Buyalskaya et al., 2023, p. 1). So, bad habits (that might derail the new behaviours) need cues, routine (time and place) and rewards to survive. Redesigning your environment to remove tempting cues or staying away from the place in which your bad habit occurs (whilst doing something else that is equally rewarding in the same timeslot) is like robbing a fire of fuel or oxygen, whilst repeating and reinforcing its replacement (Buyalskaya et al., 2023). That’s one reason it’s important to make sure your surrounding environment also matches your objectives. “If you have a goal not to eat certain foods, don’t keep them around the house to constantly tempt you,” offers Fogg (Austin, 2024).

3. Buddy-up: Research shows that partner support can be incredibly powerful when used as a force for good, so enrol a close friend or colleague to keep you accountable for the change and check in on your progress (or lack thereof) daily (Perry et al., 2016).

4. Baby-steps: Don’t make your first goals overly ambitious. Set ‘micro goals’ that are almost impossible to fail at, like one minute of exercise or meditation. Science tells us that this helps to overcome our inertia and we tend to end up doing more than planned, rather than less (Clear, 2018; Rai et al., 2023).

5. Identify carefully: Pick the right habit because, if you fail to do so, you aren’t likely to accomplish the corresponding goal. For example, exercising to lose weight without changing your diet is unlikely to result in weight loss, so, you will likely become demotivated and give up long before it becomes a habit. (Austin, 2024).

6. Track progress: “Writing down your goals and keeping track of your progress makes you much more likely to achieve them.” according to Christine Whelan, a clinical professor and consumer scientist at the School of Human Ecology at University of Wisconsin – Madison (Austin, 2024).

7. Stack the odds in your favour by redesigning your environment: “If you have an environment at home that makes exercise easy, you’ll probably work out more.” According to Fogg, the goal is to “make the unwanted behaviours hard to do and the good behaviours easy.” You can also increase your chances by doing it at the same time and place each day. Nominating a place and time where you will perform it doubles the likelihood of making that behavioural change (Milne & Orbell, 2002).

References

Austin, D. (2024). 8 Strategies to Make Your New Year’s Resolutions Stick. Retrieved January from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/premium/article/new-years-resolutions-stick?rid=90AEA894ACCA48C0129F5D6E08197A31&cmpid=org=ngp::mc=crm-email::src=ngp::cmp=editorial::add=Daily_NL_Tuesday_Health_20241231

Buyalskaya, A., Ho, H., Milkman, K. L., Li, X., Duckworth, A. L., & Camerer, C. (2023). What can machine learning teach us about habit formation? Evidence from exercise and hygiene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(17), e2216115120. https://doi.org/doi:10.1073/pnas.2216115120

Clear, J. (2018). Atomic Habits. Random House.

Gardner, B., & Rebar, A. L. (2019, 2019/4/26/). Habit Formation and Behavior Change. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.129 (Habit Formation and Behavior Change)

Harvey, A., Armstrong, C., C. , Callaway, C., A. , Gumport, N., & Gasperetti, C. (2020, 2020). COVID-19 Prevention via the Science of Habit Formation. Current Directions in Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721421992028

Lally, P., & Gardner, B. (2013, 2013/5//). Promoting habit formation. Health Psychology Review, 7(sup1), S137-S158. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2011.603640

Milne, S., & Orbell, S. (2002). Combining Motivational and Volitional Interventions to Promote Exercise Participation. British Journal of Health Psychology, 7(May), 163-184.

Orbell, S., & Verplanken, B. (2020, 2020). Changing Behavior Using Habit Theory. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108677318.013

Perry, B., Ciciurkaite, G., Brady, C. F., & Garcia, J. (2016). Partner Influence in Diet and Exercise Behaviors: Testing Behavior Modeling, Social Control, and Normative Body Size. PLOS ONE, 11(12), e0169193. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169193

Rai, A., Sharif, M. A., Chang, E. H., Milkman, K. L., & Duckworth, A. L. (2023). A field experiment on subgoal framing to boost volunteering: The trade-off between goal granularity and flexibility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(4), 621-634. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001040

Want original, well-researched articles like this on a monthly basis? Sign up for our newsletter. Subscribe and share below!